Private Foundations

This comprehensive guide provides a detailed overview of the essential requirements for private foundations. The focus includes tax law, investment activities, minimum distribution requirements, administrative expenses, IRS sections, case studies, and compliance checklists. The guide aims to ensure that private foundations remain compliant with federal regulations while efficiently managing their operations, charitable purposes, and tax obligations.

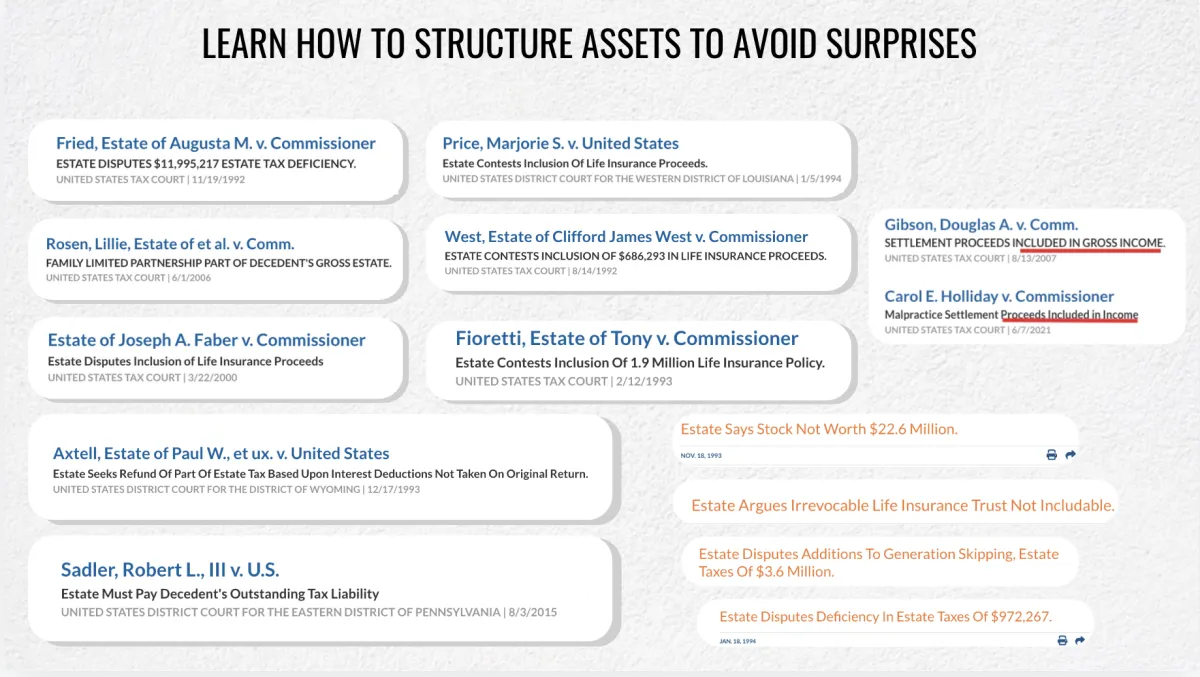

Learn how to leverage the law to your benefit.

Requirements for Full Transfer to a Foundation

Irrevocable Transfer of Ownership

When a donor contributes assets to a foundation, they must relinquish all control over the asset. For example, if a donor contributes a piece of real estate, they can no longer use, lease, or sell the property and reap the personal rewards or profits from the transaction, nor treat it as their own personal asset.

In the case of Estate of O'Keeffe v. Commissioner (1992), the court ruled that the transfer of assets to a foundation must be irrevocable for it to qualify as a charitable deduction.

Proper Valuation of Assets

Assets donated to a foundation must be accurately valued to prevent overvaluation, which could lead to improper tax benefits.

For instance, if someone donates a valuable painting, a qualified appraiser must determine its fair market value (FMV). Failure to properly appraise the value of non-cash donations over $5,000 can result in IRS penalties.

Written Acknowledgment from the Foundation

The foundation must provide a written acknowledgment, especially for donations over $250. For example, a donor who contributes stocks worth $100,000 should receive a detailed acknowledgment from the foundation specifying the number of shares, FMV, and a statement that no goods or services were provided in return.

Exclusive Use for Charitable Purposes

Donated assets must be used solely for the foundation's charitable mission. For instance, if a donor contributes land, the foundation must use it for purposes like building a community center, not for personal gain. Any use for non-charitable purposes could violate IRS rules and result in penalties.

IRS Reporting Compliance

Donors and foundations must report the donation and its use through IRS filings, including forms like 8283 for non-cash contributions and 990-PF for foundation activities. Failure to report accurately, as seen in cases involving improper IRS filings, can lead to audits and financial penalties.

No Substantial Benefits to Donor

The donor cannot receive any significant benefits from the donation. For instance, if a donor contributes to a foundation and receives a free vacation in return, the IRS could disqualify the donation. This occurred in cases where charitable deductions were denied due to improper compensation.

Immediate Transfer of Legal Title

The title or legal ownership of donated assets must be transferred immediately to the foundation. For example, if a donor gives stock to a foundation, they cannot retain voting rights or control over those shares.

No Retained Interests or Conditions

Donors cannot impose conditions that give them continued control over the asset. In one court case, a donor's attempt to retain control over a building after donating it to a foundation resulted in disqualification of the tax deduction.

Use of Qualified Appraisals for Non-Cash Donations Over $5,000

For non-cash donations exceeding $5,000, the IRS requires a qualified appraisal to substantiate the claimed value. For example, if a donor contributes valuable artwork, they must obtain an appraisal from a certified appraiser to comply with IRS requirements.

Investing Activities of Private Foundations

Prudent Investment Standards

Foundations are expected to invest conservatively and responsibly. For instance, if a foundation invests its assets in high-risk startups or speculative markets, it could violate prudent investment standards. A practical example involves a foundation investing in bonds rather than high-risk stocks to balance risk and return.

Avoidance of Jeopardizing Investments (IRC Section 4944)

Jeopardizing investments are those that put the foundation’s assets at undue risk, potentially threatening its ability to fulfill its charitable mission. For example, in Commissioner v. Wemyss (1990), the IRS imposed penalties on a foundation that invested in speculative real estate, violating the jeopardizing investments rule.

Program-Related Investments (PRI)

Foundations can make PRIs to further their charitable missions. For example, a foundation might provide low-interest loans to a nonprofit organization working on affordable housing projects. In contrast, an investment in a for-profit venture not aligned with the foundation's mission would not qualify as a PRI.

Minimum Distribution Requirement (MDR)

Foundations must distribute at least 5% of their net investment assets annually. If a foundation has $10 million in assets, it must distribute at least $500,000 annually in grants or qualifying expenses. Failure to meet the MDR could result in a 30% excise tax on the amount not distributed.

Avoiding Self-Dealing (IRC Section 4941)

Self-dealing occurs when a foundation engages in financial transactions with insiders or disqualified persons. For example, if a foundation leases office space from one of its directors, that transaction may be considered self-dealing and result in a 10% excise tax. United States v. Wells Fargo Bank (1981) highlighted penalties for improper self-dealing transactions.

Prohibition on Excess Business Holdings (IRC Section 4943)

Foundations are prohibited from holding more than 20% of the voting stock in a for-profit business. For instance, if a foundation owns 25% of a corporation’s stock, it must divest some of that holding or face a tax penalty. This ensures foundations do not gain undue influence over for-profit entities.

Tax on Investment Income (IRC Section 4940)

Foundations must pay a 1.39% excise tax on their net investment income, which includes interest, dividends, rents, and capital gains. For example, if a foundation generates $500,000 in investment income, it would owe approximately $6,950 in excise tax.

Administrative Expenses for Foundations

Investment Management Fees

Foundations often hire professionals to manage their investment portfolios, and the fees for these services are considered deductible administrative expenses. For example, a foundation may pay 1% of its assets annually to a financial advisor for managing its investment strategy.

Legal and Accounting Fees

Legal and accounting services required for maintaining compliance with IRS rules are allowable expenses. For instance, hiring an attorney to help the foundation set up a new charitable project or an accountant to file the annual 990-PF are examples of acceptable expenses.

Operating Costs (Rent, Utilities)

The foundation may deduct reasonable expenses associated with maintaining an office, such as rent and utilities. However, the expenses must be aligned with the charitable mission. If a foundation rents luxury office space far exceeding reasonable costs, the IRS may scrutinize these expenses.

Board Expenses (Travel, Meetings)

Board members can be reimbursed for reasonable travel and meeting expenses related to their foundation duties. For example, if a board member travels to attend an annual meeting, the cost of flights and accommodations can be covered, but excessive or luxury accommodations could be questioned.

Staff Salaries and Benefits

Salaries paid to employees who directly contribute to the foundation’s charitable activities are allowable expenses. For example, the executive director of a foundation responsible for managing grants can be paid a reasonable salary. However, excessive compensation, such as paying a relative a high salary for minimal work, could trigger IRS audits.

Filing and Compliance Fees (IRS Form 990-PF)

Foundations are required to file Form 990-PF annually, and the costs associated with filing, such as accountant fees, are deductible. Failing to file on time can result in penalties.

IRS Sections Relevant to Private Foundations

IRC Section 4940: Tax on Investment Income

Private foundations must pay a 1.39% excise tax on their net investment income, which includes dividends, rents, interest, and capital gains.

IRC Section 4941: Self-Dealing Rules

This section prohibits private foundations from engaging in financial transactions with insiders, such as lending money to or leasing property from disqualified persons (e.g., board members). In United States v. Wells Fargo Bank (1981), the court imposed penalties for self-dealing violations.

IRC Section 4942: Minimum Distribution Requirement (MDR)

Foundations must distribute at least 5% of their assets each year for charitable purposes. Failure to do so can result in excise taxes.

IRC Section 4943: Prohibition on Excess Business Holdings

Foundations cannot own more than 20% of the voting stock in a for-profit company.

IRC Section 4944: Jeopardizing Investments

Foundations must avoid high-risk investments that could jeopardize their financial stability. For example, investing heavily in speculative ventures could lead to penalties.

IRC Section 4945: Taxable Expenditures

Foundations are prohibited from making grants to individuals for non-charitable purposes or for lobbying activities.

Case Studies on Foundation Rules and Investments

Estate of O'Keeffe v. Commissioner (1992)

This case clarified that legal fees and administrative expenses tied to a foundation’s charitable operations are deductible. The court ruled that these expenses were necessary and aligned with the foundation’s mission.

Keller Family Foundation v. Commissioner (2004)

Excessive compensation paid to a family member serving as an executive was disallowed as a charitable deduction. The IRS ruled that the compensation was not reasonable and was therefore subject to excise taxes.

Diedrich v. Commissioner (1982)

In this case, a donor gifted shares to a private foundation but received tax benefits in return. The court ruled that this constituted a taxable gift because the donor retained economic benefits from the transaction.

Ford Foundation Controversy (1970s)

The Ford Foundation was scrutinized for its charitable practices, leading to significant reforms under the Tax Reform Act of 1969. This case introduced the 5% Minimum Distribution Requirement (MDR) for private foundations to ensure they actively contributed to charitable causes.

Checklist for Foundation Compliance

Ensure the 5% Minimum Distribution Requirement is met each year by distributing grants or spending on qualifying expenses.

Avoid jeopardizing investments that pose undue risk to the foundation’s financial stability.

File IRS Form 990-PF on time to report the foundation’s activities, financials, and grant distributions.

Avoid self-dealing by not engaging in transactions with disqualified persons, such as board members or major donors.

Maintain proper documentation for all charitable activities, grants, donations, and program-related investments.

Obtain qualified appraisals for non-cash donations exceeding $5,000 to support claimed values.

Pay the 1.39% excise tax on net investment income, including interest, dividends, and capital gains.

Follow the prohibition on excess business holdings, ensuring the foundation does not own more than 20% of the voting stock in a for-profit company.

Learn The Tax Code™ & Leverage The Law To Your Benefit

Tax Law Training Program For Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Professionals

TAX LAW

We cover several different concepts that dive into the nuances of the tax code and how different layers of taxes are going to impact every dollar that you have earned and generated.

Learn how the law works to make more sound financial and legal decisions in your business and personal life.

LEGAL ENTITIES

Discover how different legal and estate planning entities operate and how you can use them to reduce your estate size, lower personal risks, and lower immediate and future tax obligations.

The goal is to help you spot gaps in your existing legal entities or areas where you are exposed so you can leverage a combination of entities to fix leaks and gain more tax breaks.

Learn from case studies and court cases

There is no better way to learn the law than to actually read case studies and sections of the code. You will learn how to read different tax code, how to read the right case studies, what tests and logical analysis the court will use in a lawsuits, and how to avoid mistakes that can erode your wealth.

There is no point in setting up all sorts of complex legal entities if you do not understand how the law operates and how those entities are going to be taxed later down the line.

Free Webinar Preview

Here is a pre-recorded sample of the live workshop and webinar covering tax law, legal entities, and the practical strategies that you could be deploying in your business and personal life.

Schedule a call to discuss the details of the workshops and the startegies covered in these workshops

Whether you are an entrepreneurs or investor interested in learning these strategies and implementing them in your own life, or you are an attorney, accountant, financial advisor, insurance agent, or real estate professional looking to add more value to your clients - these workshops can be catered to fit your particular goals and needs.

Copyrighted Material © All Rights Reserved. 2024. Law and Tax Foundation™. Property of Estate Law Training Center, a 501c3 nonprofit organization. EIN: 92-0560457

IMPORTANT: LAW AND TAX DISCLAIMER

Law and Tax Foundation is a nonprofit organization that conducts and published legal and tax research. We are not a law firm, accounting firm, financial advisory firm, family office, or a consulting firm. Any information, content, and services provided are strictly educational and informational in nature and do not constitute legal or tax advice. The law changes constantly and information found on our website could be outdated based on the publication date. Please consult an attorney or CPA in your area for any specific legal or tax related services or help. No attorney-client relationship is formed by participating in any workshops, or by communicating with us.